The Bayesian interpretation of probability is the interpretation that is (usually) used to justify Bayesian statistics. It bases the use of probability on the belief of rational agents, believing that probability is used to rigorously quantify our uncertainty of various propositions. It is typically contrasted with the frequentist interpretation of probability.

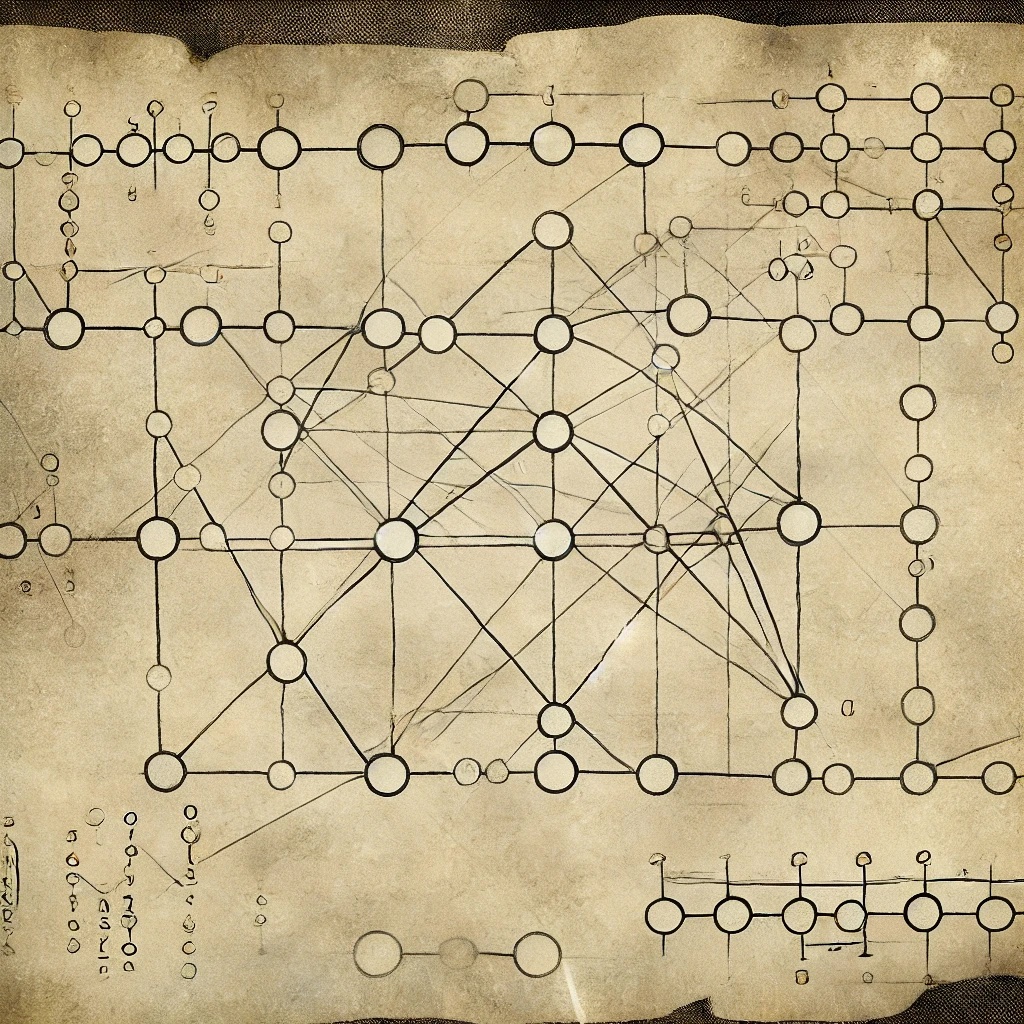

Bayesians treat propositions as random variables, and treat belief in propositions as a probability measure. One begins with a prior belief in a proposition, and then updates it based on the evidence.

There are two major Bayesian schools: Objective Bayesianism (also called logical probability) and subjective Bayesianism. Objective Bayesians take the view that there is an objectively correct prior to place on a proposition; subjective Bayesians that you can use whatever prior you want. Objective Bayesians typically use Cox’s theorems to define rationality, which posits that the beliefs of a rational agent obey certain probabilistic axioms.

The tradition of (subjective) Bayesianism dates back to Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat. In correspondence with Fermat, Pascal claimed that states of uncertainty can be quantified using probability. Thomas Bayes then showed how to update these probabilities in light of new evidence, though it’s unclear how comfortable Bayes would have been with modern Bayesianism. Laplace recognized the importance of Bayes’ theorem and applied to all sorts of statistical problems, while also favoring a Bayesian-like interpretation of probability.

In the modern era, the two figures most associated with the subjectivist school are Frank Ramsay (see his 1926 paper truth and probability) and Bruno de Finetti (see his 1937 paper La prévision: ses lois logiques, ses sources subjectives). Other key figures in this tradition are LJ Savage and JL Doob.

The father of objective Bayesianism is arguably Harold Jeffreys, though Keynes introduced many of the concepts first. But Keynes didn’t think that all beliefs were quantifiable, setting him apart from most Bayesians. Other notable objective Bayesians are Carnap, ET Jaynes, and Cox.

Personally, I think the Bayesian interpretation is wrong. It is neither descriptively nor normatively true that people have beliefs that obey the axioms of probability. Indeed, this isn’t even possible, since the sample space isn’t well-defined: you would need to place a probability on everything proposition that could possibly be uttered. Moreover, evidence is quantifiable in small-worlds only, not in large-worlds, so updating your belief in a proposition in a large “based on the evidence”, is a non-starter. It is also circular.